An Interview with Emil Jeansson, Chemical Oceanographer

By Emil Jeansson, NORCE | December 12, 2023

Emil Jeansson is a Chemical Oceanographer at NORCE Norwegian Research Centre in Bergen, Norway.

Is it true that you can determine the age of water from a sample in the ocean?

Yes, as a chemical oceanographer, I mostly work with transient (i.e. time dependent) tracers in the ocean, especially chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), which are man-made chemical components present in the atmosphere, and that are absorbed by the surface of the ocean. We know the atmospheric history of these compounds very well—how their concentrations have changed in the atmosphere over time due to human activities. This is important because when we measure the concentrations of these tracers at different depths in the ocean, we relate these concentrations to their atmospheric history. When we know, or assume, the degree of mixing that a water parcel experiences as it descends from the ocean surface to larger depths, in the studied region, we can calculate back what year that water was in contact with the atmosphere. The time that has passed is then defined as the “age” of that water mass.

What is the oldest water

you have ever analysed?

I work mostly in the Nordic Seas (the region between Greenland, Iceland, and Norway), the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic. These are regions with relatively “young” waters compared to many other regions in the global ocean. The oldest waters I have analysed have been in the deep parts of the central Arctic Ocean, where ages of roughly 500–600 years can be found. The oldest waters in any ocean can be found in the deep parts of the northern Pacific Ocean, where the waters have been estimated to be approximately 1000 years old.

How does determining the age of water help us understand climate change?

The properties of the surface water reflect the atmosphere at the time they are in contact. When a parcel of water leaves the surface, because it gets denser, it brings these climate signals of the atmosphere to the interior ocean. This includes the concentration of man-made carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, what we call anthropogenic CO2 or anthropogenic carbon. We cannot measure the concentration of anthropogenic carbon, but we can calculate it using different methods. Our tracer-based method that lets us determine the age can also be used to estimate concentrations of anthropogenic carbon. The ocean presently takes up about 25% of the emitted CO2 from anthropogenic activities. There are two sides of this: the good thing is that it mitigates climate change – since without the uptake by the ocean more CO2 would remain in the atmosphere, thereby increasing the green-house effect – but the additional carbon added to the ocean also leads to ocean acidification, which has a negative impact on some of the biology. Thus, it is important to keep track of how much man-made CO2 has been stored in the ocean, and how this storage changes with time.

Hence, it is important to conduct measurements of transient tracers in the ocean. However, it is a highly specialised analysis, and there are not many groups across Europe that actually work with this method because they do not have the expertise, as of today.

How do you solve that problem then? Share the knowledge and expertise?

This is one of the main objectives of the EuroGO-SHIP project and its aim to provide access to shared facilities and training of best practices. Transient tracer measurements and other specialised measurements are just examples, but this does also entails specialised equipment.

It doesn’t always make sense for every single group or country to have certain instruments in place at all times. They might not use it enough to justify the cost, or they want the chance to test its value before purchasing. So this is one of the aims of the EuroGO-SHIP project—to establish both the requirements of the hydrographic community and to define a way to share expertise and equipment.

I am participating in Work Package 2 where I’m leading Task 2.1, which is about developing shared facilities, a support service for the hydrographic community in Europe. We are reaching out to communities across Europe to determine exactly what their needs are and to see how we can help, whether it is to fill skill gaps for certain types of analysis, to facilitate equipment sharing, or training of the next generation of scientists on things like cruise logistics.

What are some of the things you must consider with sharing facilities?

For an institute in one country to loan and send, for example, an analytical instrument, to another institute in another part of Europe, there are a lot of things to consider. Insurance for one—there needs to be a cost model in place for different types of services and destinations.

We also have to consider customs and when hazardous materials are involved—there are a lot of requirements on how to send and deal with that. For everything, there’s a long list of items that need to be checked off. And a process for this is one of the things that will be an important legacy of EuroGO-SHIP – that we will have identified the requirements, we will have mapped out all the considerations and we will have a tested method to facilitate the access to the different services in the shared facilities.

Once the equipment has arrived, what kind of training and knowledge transfer takes place?

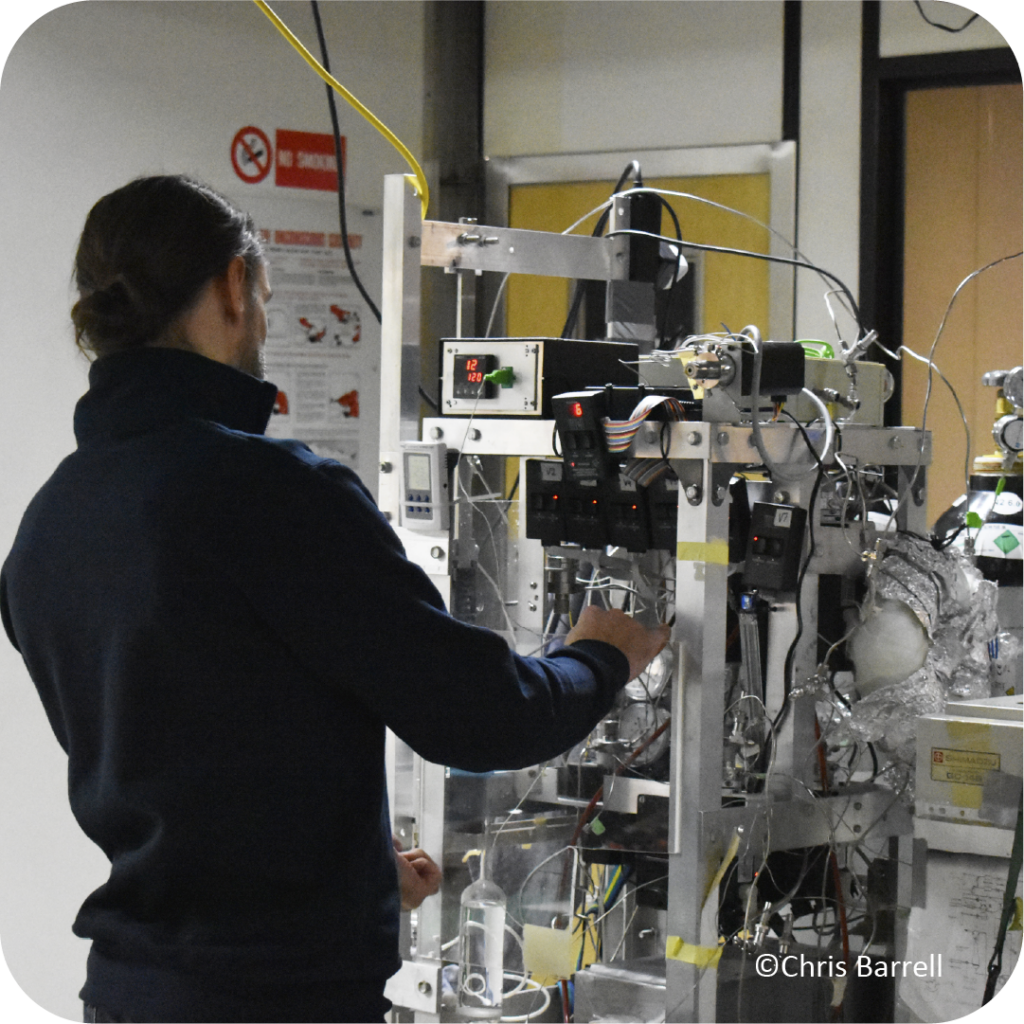

There are different scenarios for different types of situations – equipment and analysis—so it starts with understanding the requirement and then providing the best training plan to share expertise. We have sent our EuroGO-SHIP partners from two different organisations (working in the Mediterranean and the North Atlantic) to the Black Sea to train on methods and equipment and we’ve had successful results (A Tale from a Budding Oceanographer) with the analysis as well as piloting the actual sharing process. We also have plans on how to add transient tracer measurements to certain UK cruises, which include training of UK staff on these measurements during, and possibly before, the cruises.

And in addition to sharing knowledge and training on analysis, there is a strong need to support the next generation of scientists, to mentor them on what is new in marine science in general, to facilitate visits to labs, and to help them with things like cruise logistics for scientific cruises. There is a lot of information regarding logistics that scientists need to know, and this can be a steep learning curve for somebody just starting their career. So it is important to make berths available on research cruises so early career scientists can come along and be mentored on logistics, water sampling techniques, equipment, analysis at sea, everything really.

And thus…you ensure the future of scientists who can determine the age of water?

It is important to ensure the knowledge transfer of all needed observations and measurements to the next generation of scientists. The EuroGO-SHIP project can really make a difference in this regard. Transient tracer measurements are certainly on the radar due to the few groups conducting this type of work. Luckily there are interests among younger scientists to take this on. It is a lot of work, but it can really add important knowledge for different ocean and climate change studies, so hopefully we can inspire more along the way.

By Emil Jeansson, NORCE | December 14, 2023

About the author

Name: Emil Jeansson

Work Package: WP’s 2

Organisation: NORCE, Norway